Why Are Shinto Prayers Still Spoken in Archaic Japanese?

On Ritual, Language, and the Space Between Kami and Human

Old Words, Sacred Sounds

After writing about ema and the many languages people use to speak to the kami, I was left with another question—one I often get from students and visitors:

If we can write to the gods in any language, why do priests chant in such old-fashioned Japanese?

It’s a good question.

The answer lies in what norito are, how they work, and what they mean—not just to those who hear them, but to the rituals themselves.

This post is a personal reflection on that question, drawn from my experience as a priest, and my awe for the ancient words I’ve been entrusted to speak.

Why Are Norito Spoken in Archaic Japanese?

In Shinto, words are not merely tools of communication. They are offerings.

When we recite a norito—a sacred prayer—we do not speak casually. We cross a threshold into a different kind of language: older, more deliberate, and deeply reverent.

Many visitors to Japan are surprised to learn that norito are not composed in modern Japanese. Instead, they are written in a poetic, elevated style known as Yamato kotoba—native Japanese words that trace back to the earliest layers of the language.

Why? Why not speak plainly, in the language we use every day?

What Is a Norito?

A norito is a ritual prayer offered by a Shinto priest during ceremonies. It carries praise, gratitude, and specific wishes—spoken in an ancient, formal register. We recite norito slowly and gently, not as conversation and not as performance, but as something quieter.

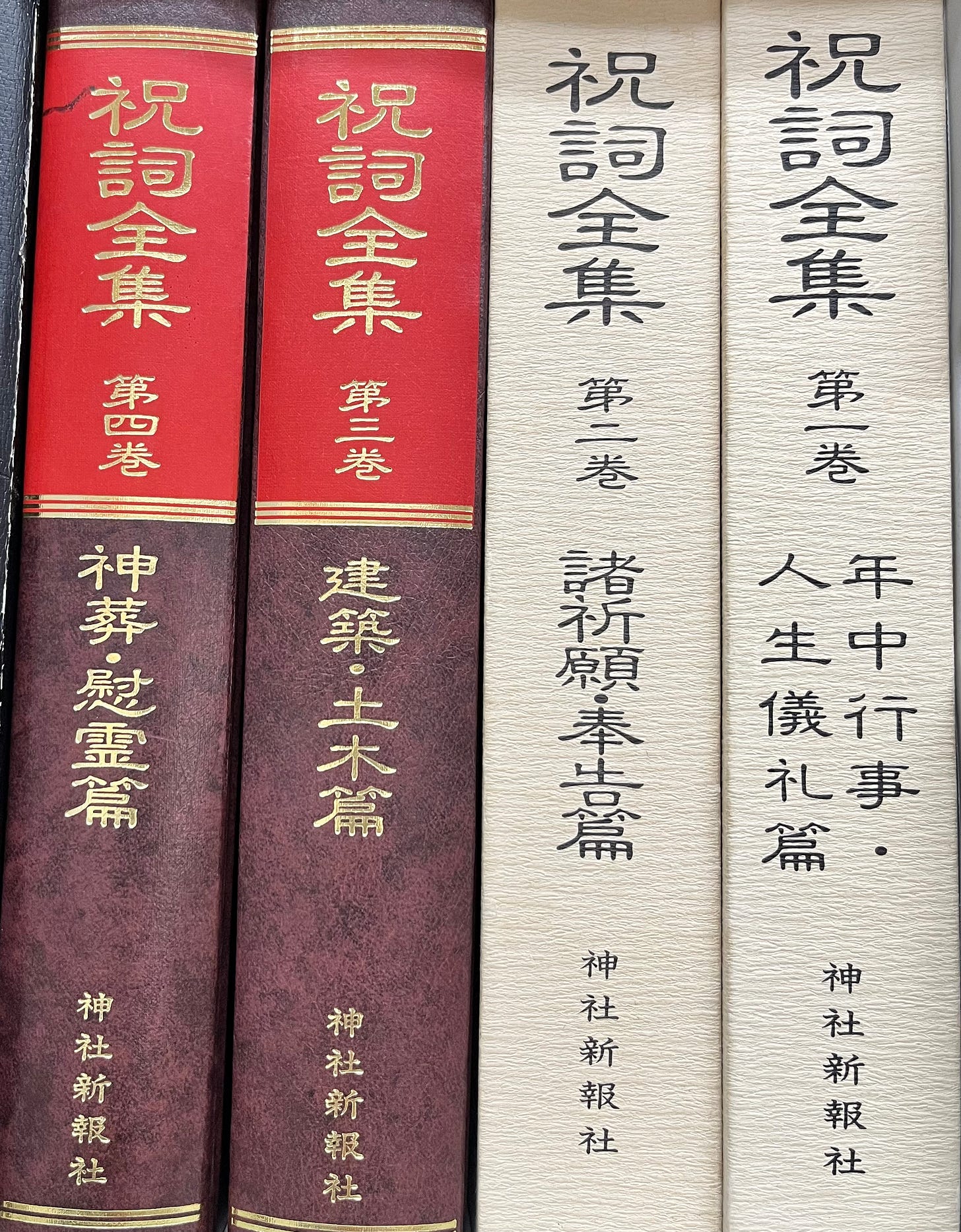

Unlike the fixed liturgies of some religions, norito are composed anew for each ritual. In the daily prayers known as kigansai, the hopes of the individual or family are written directly into the text. These may include traditional blessings for family harmony or romantic connection—but also modern desires: passing a university exam, succeeding in a job interview, or the safety of a large engineering project.

The content of the norito shifts with the times. But the language we use to speak these wishes remains unchanged.

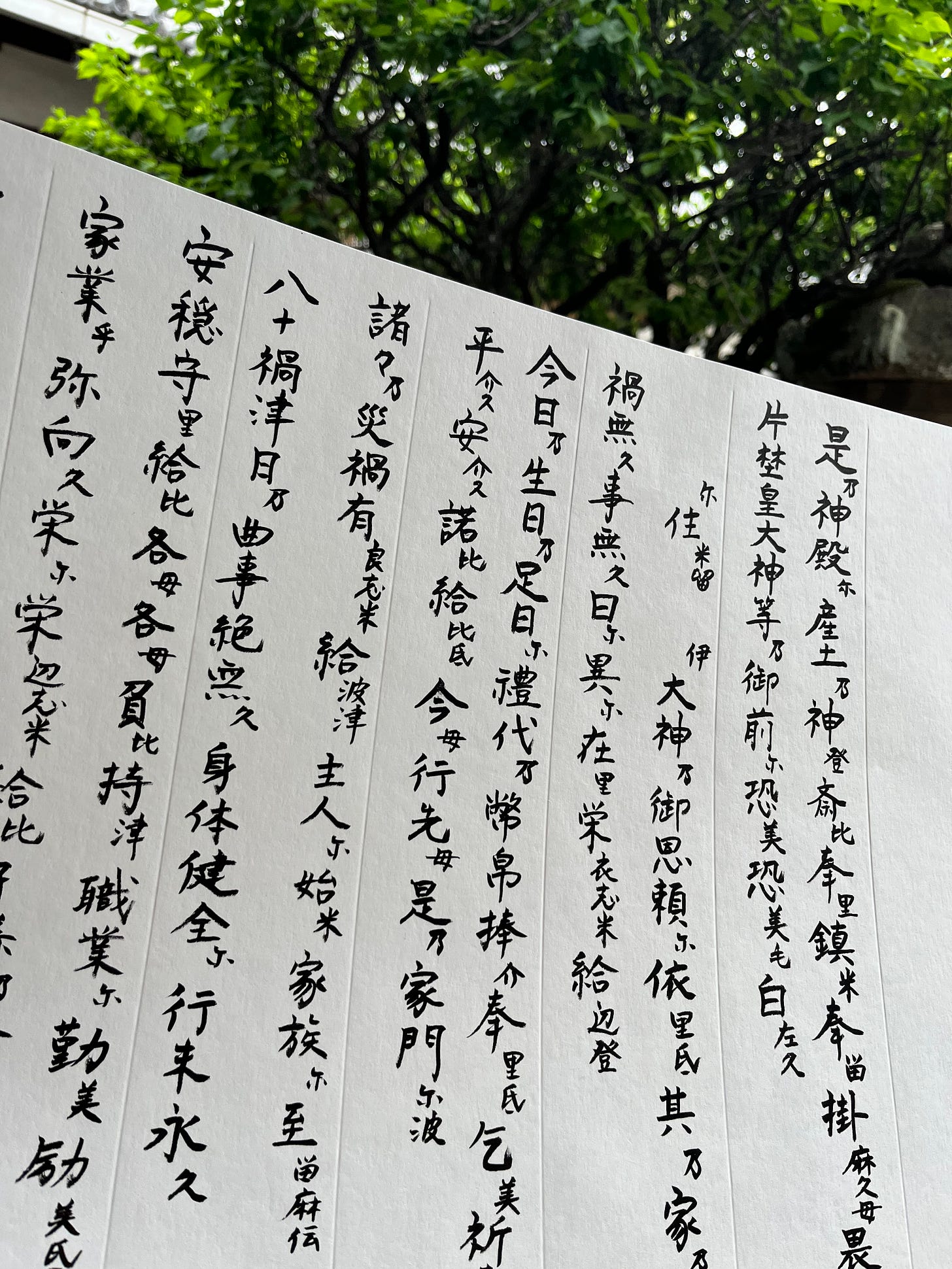

Each norito is written in Yamato kotoba with black ink on white paper, folded in the traditional seven-fold style, opened gracefully before the kami, and then offered aloud with care and reverence.

Why Archaic Japanese?

As priests, we must complete formal training in both norito composition and norito reading, so that we can write and recite prayers in this classical form. In over twenty years of daily service at my shrine, I have never once heard a norito recited in modern Japanese.

So when someone asked me, “Why can’t you just say it in regular Japanese?”—I had to stop and truly reflect.

Shinto has no single holy book. We have no fixed doctrine, no theology of sin or salvation. So what anchors our practice? I believe it is this: continuity. What has been repeated over centuries, what has endured, becomes sacred through time.

Language is alive. I myself sometimes have no idea what my teenage son and daughter are even talking about. But inside the shrine—this ritual vessel—certain words have been lovingly preserved. The ancient vocabulary of Yamato kotoba has been carried forward, like heirlooms. These words are not just linguistic fossils. They are offerings in themselves. They are sacred because they have been cherished.

The wishes we pray for may be utterly contemporary—digital success, project funding, even a smooth PowerPoint presentation—but we offer them in ancient words.

Why? Because we feel that the more timeless the form, the closer it draws us to the divine. The kami listen not only to the meaning, but to the spirit behind the sound. We feel that old words carry that spirit more clearly. They resonate. They groove with the sacred.

A Language That Lives Between Worlds

In many countries, Latin is seen as a “dead language.” But as one reader who studied Catholicism in Italy reminded me, that isn’t always the case. In Italy, Latin is still taught in schools. You see it carved into churches, woven into artworks, even spray-painted in graffiti. And because its rhythm echoes modern Italian, it can be hard to tell—just for a moment—whether a mass is being spoken in Latin or the vernacular. Latin lives on, just beneath the surface.

I feel something similar with norito. The ancient words of Yamato kotoba may no longer be spoken in daily life, but they haven’t disappeared. Like roots under the forest floor, they nourish the present quietly, invisibly. Neither fossil nor fantasy, these words still carry power—not despite their age, but because of it.

The Sound of Sacred Dialogue

A norito is not just a message—it is a moment. A live exchange between humans and the kami. We do not chant it like poetry, nor read it like prose. We offer it as sound. In Shinto, to voice sacred words is to enter communion. The kami hear not only the words, but the intention woven into the breath.

As priests, we stand between the petitioner and the divine. We do not speak for ourselves. We lend our voices to carry someone’s wish upward, wrapped in reverence.

That is why, even when the content is modern, the form must be ancient. Because this is not like writing a wish on an ema plaque—a message left to sway in the wind.

A norito is a sacred concert, a quiet and living ritual in which human and kami meet, in harmony.

And in that moment, the words must be at their most sacred.

P.S. — A Note for Future Reflections

One day, I’d like to reflect on whether norito could be offered in English—or in local languages outside Japan. It’s something I continue to think about.

If You’re New Here

You might also like a previous post:

🪵 Can Kami Understand English?

A reflection on ema, prayer, and the gentle ways kami may listen to us.

When I Post

I usually publish on Tuesdays, with occasional reflections on seasonal or ceremonial days from the Shinto calendar.

Thank You

If this piece resonated with you, I’d be grateful if you shared your thoughts in the comments—or simply returned again sometime.

Thank you, always, for reading.

"The ancient words of Yamato kotoba may no longer be spoken in daily life, but they haven’t disappeared. Like roots under the forest floor, they nourish the present quietly, invisibly. Neither fossil nor fantasy, these words still carry power—not despite their age, but because of it."

This particular section really resonated with me and reminds me of how many people are working all over the world to preserve their cultural and linguistic traditions, because I think we as humans see the inherent value in antiquity! Thanks again for another wonderful article, I look forward to reading what you write next!

It's not *as* old but I think Christians who prefer the English of the King James bible or the (roughly similar time) Anglican Book of Common prayer understand why instinctively. Likewise with the Orthodox who use Old Church Slavonic instead of current Russia, Ukrainian etc.

It's not just tradition, it's a clear separation of the divine from the mundane world.