A Prayer That Grows with Us

When we pray for children, what are we truly asking for?

In Shinto, there is a kind of ritual known as kigansai(祈願祭)—a personal ceremony in which a priest conveys a worshipper’s wishes to the kami(神, deities)through a sacred norito(祝詞, ritual prayer). The content of each norito shifts depending on the nature of the prayer. Among these rituals is a special category called jinsei girei(人生儀礼, rites of passage), which mark particular ages throughout life.

For children, these ceremonies are prayers for safety and health. For young adults, they are celebrations for the beginning of contributions to society. And for adults, they are markings for transitions into greater responsibility, or seeking protection from misfortune.

In this post, I’d like to respond to a reader’s request by focusing on Shichi-Go-San(七五三), the 7-5-3 celebration for children. This tradition includes visits to a jinja (Shinto shrine), rituals of prayer, and beautiful clothing rich in symbolism. But it also opens the door to something deeper: the traditional Japanese way of counting age, the cosmological view of numbers, and the belief that children are still close to the divine.

We’ll also explore the chigo gyōretsu(稚児行列), a different kind of ritual where children become the ones who lead the kami through the streets.

Whether or not we have children of our own, we were all once small beings—watched over, hoped for, and carried forward by someone else’s quiet prayers. These rituals are not just about children. They are windows into a way of seeing life itself: as something sacred, unfolding step by step, through a relationship with the unseen.

When We Pray at Seven, Five, and Three

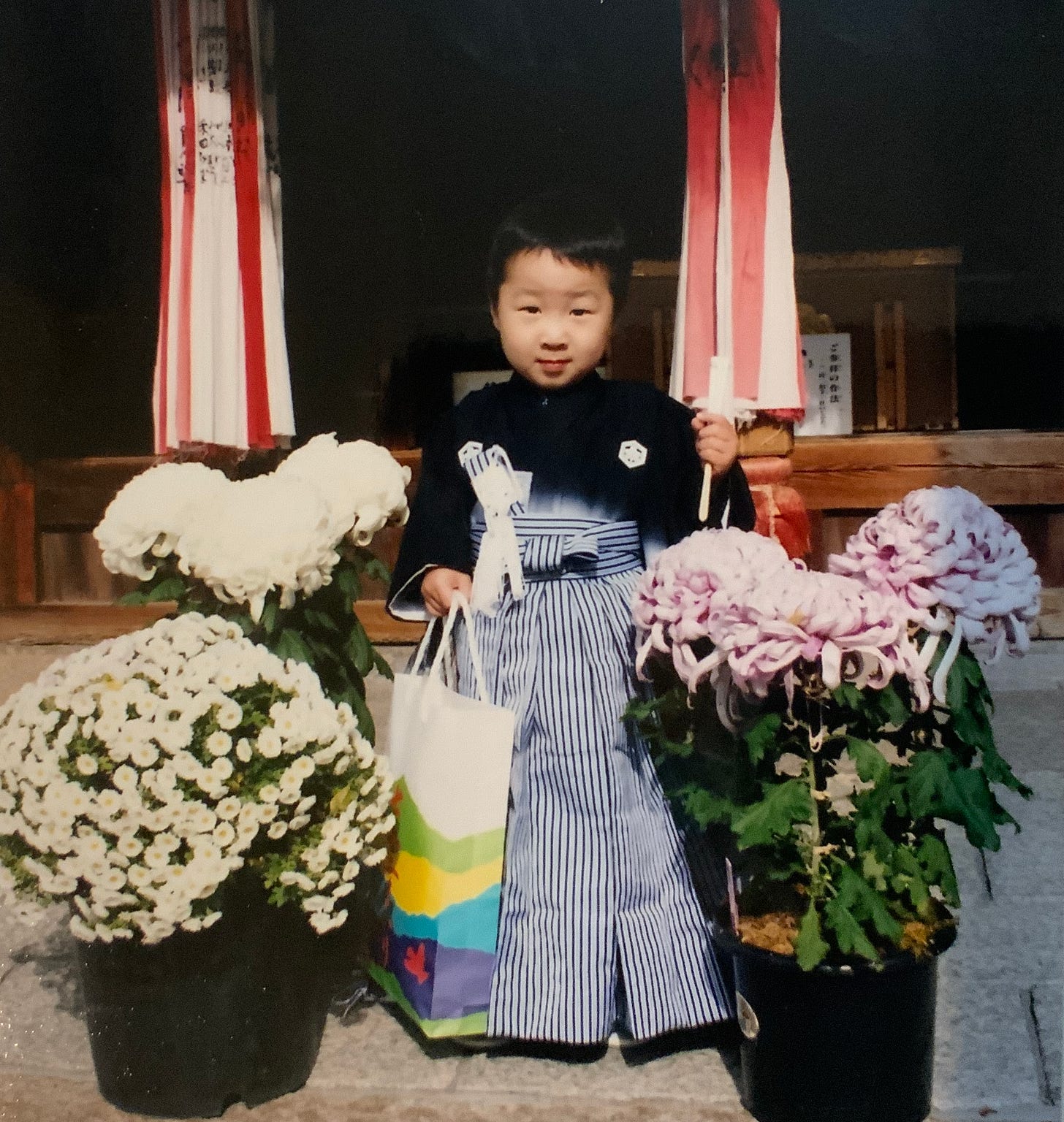

Shichi-Go-San (7-5-3) is a prayer ritual in which children of ages 3, 5, and 7—dressed in traditional kimono(着物)or hakama(袴)—visit a jinja with their families to pray for their continued healthy growth. It is one of Japan’s most widely practiced celebrations. According to statistics from photo studios, about 70–90% of children in the target age group participate in Shichi-Go-San ceremonies.

Children dressed in age-appropriate ceremonial clothing visit jinja or temples to receive blessings, regardless of whether the family holds strong religious beliefs. November is considered the peak season for these visits.

The ritual follows the same basic flow as a kigansai, but in addition to ofuda(お札, talismans)and omamori(お守り), protective amulets), children often receive symbolic gifts like chitose-ame(千歳飴), a long stick-shaped candy representing longevity, as well as stationery or traditional toys.

Its roots are ancient and spread across all regions of Japan, so it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when it began.

The hakama-gi no gi(袴着の儀)was historically a ceremony marking the first time a child wore hakama. Records of this practice among the aristocracy date back to the mid-Heian period (10th century). Meanwhile, folk traditions celebrating children's growth also existed among common people from earlier times.

Counting Years, Receiving Time

Traditionally, Japanese age was counted using kazoedoshi(数え年), where a child is considered one year old at birth, and then everyone turns a year older on January 1st. This custom reflects the belief that each New Year brings a new year of life granted by the Toshigami-sama(年神様, deity of the new year). While modern Japan uses the Western-style man-nenrei(満年齢, actual age), most life rituals like Shichi-Go-San still use kazoedoshi.

The Meaning of Numbers

In this worldview, numbers are not just quantities but carry spiritual qualities. Odd numbers are considered yang(陽)—bright, active, auspicious. Even numbers are yin(陰)—quiet, passive. This concept originates from ancient Chinese onmyō gogyō(陰陽五行, yin-yang and five elements) thought, which deeply influences Japanese tradition.

Just remember: odd = yang = lucky. These are the numbers used for children’s growth rituals.

Why Are Odd Numbers Considered Auspicious?

You might wonder, “Why are odd numbers considered auspicious?” This is just my personal reflection, but perhaps when two people share something and the number is odd, one piece remains. That leftover can be offered to the kami. In that simple act, the sacred is remembered.

Samurai Seasons: Why We Celebrate in November

A widely accepted theory traces the November timing of Shichi-Go-San to the Edo period (17th–19th century), when Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the fifth shogun, held a hakama-gi(袴着)ceremony for his son in November. As the Tokugawa family stood at the top of the samurai class and ruled the country as shoguns, their customs had a powerful influence on society. This particular timing gradually spread among the common people.

During this period, the garments worn for Shichi-Go-San took on the style traditionally worn by children of samurai families—the ruling warrior class of Japan. Boys wore haori jackets and hakama, while girls wore kimono. This clear gender-based distinction in attire has continued into the present day.

While the ritual could technically take place at any time of year, November remains the most common month due to the cool weather (ideal for wearing the garments) and seasonal factors like the production of chitose-ame.

Milestone Ages and Their Ceremonies

The original meaning behind Shichi-Go-San now lies in the customs of the samurai class and traditional age-based celebrations (toshi-iwai). Today, however, that original significance is reflected primarily in the traditional garments worn for the rituals.

Age 3 — beginning to grow out hair (kamioki no gi 髪置きの儀) for boys and girls

Age 5 — first time wearing hakama (hakama-gi no gi 袴着の儀) for boys

Age 7 — first time wearing an obi (obi-toki no gi 帯解きの儀) for girls

The kamioki no gi at age three marked the beginning of growing out a child’s hair, which had previously been shaved for hygiene. In the Heian period, when girls also wore hakama, the hakama-gi no gi ceremony was performed for both boys and girls.

Rituals That Grow with the Child

As part of this beautiful cultural tradition, some families remake the mother’s kimono into the celebratory attire for the seven-year-old child. Others pass down garments like kimono or hakama from generation to generation.

At the same time, many children and their parents opt for rental clothing or services provided by photo studios, which offer full sets of traditional attire along with dressing assistance.

Participating in Shichi-Go-San does not require wearing traditional garments. Some children attend the ceremony in modern clothes such as dresses or suits. Others wait until their man-nenrei rather than kazoedoshi to participate. Because a child born on December 31st would, according to the traditional 'counted age' system, receive a new year from the Toshigami deity the very next day and become two years old, even though they may not have grown enough to wear the traditional attire typically worn at the counted age of three.

Ultimately, Shichi-Go-San, like all kigansai, allows for flexibility. The ritual should take the shape that suits the prayer. Even so, the fact that many still choose the traditional style shows how deeply the Japanese value continuity. Like other kigansai, Shichi-Go-San is also open to overseas visitors. Perhaps knowing this background will make the experience all the more meaningful.

Before Seven, Wondering with the kami

In earlier times, medical care and nutrition were limited, and many children died before reaching school age. People believed that a child’s soul (tamashii 魂) was not yet firmly settled in the body—it could slip away at any time. In this way, children were seen as still belonging to the divine realm.

There was even a saying: “Before seven, still with the kami”(七つ前は神のうち).

This expression reflects the belief that young children's souls are not fully anchored in their bodies—they are still fluttering like the wind, sometimes dwelling in the body, sometimes not. It’s as if the soul, like the kami themselves, moves freely, and the child’s body is a kind of himorogi(神籬, sacred enclosure) that the soul only sometimes inhabits. This worldview suggests that children are not fully part of the human world until about age seven, and thus their lives are celebrated and prayed for with special care.

Therefore, from the moment of birth to age seven, families held repeated rituals to mark growth and pray for continued life.

Sleeping Beside the Sacred

When my twins—a son and a daughter—were young, we all slept together until they were ten. Our house was small, with no beds—just tatami(畳)mats and futon(布団)mattresses spread across the floor at night. (In Japan, it’s not considered unusual at all for parents and children to sleep together. Typically, children share a futon or room with their parents until around the age of seven.)

After finishing the day’s chores, preparing the next day’s bento(弁当), and closing my journal, I would quietly slip into the irregular space between their restless little bodies. My back ached, but my soul settled. Now that my children are teenagers and sleep far away down the hallway, I look back and feel sure: children are close to the kami, and it was their sacred nearness that gave me such comfort.

When Children Lead the kami

While Shichi-Go-San is a personal rite of passage celebrated at specific ages, there is another tradition in which children participate not for their own milestone, but as sacred figures within a larger community ritual.

In many Shinto shrine festivals (reisai 例祭), children dress in elegant ceremonial attire and join processions through the streets as chigo, or sacred children. This practice, known as the chigo gyōretsu(稚児行列), is based on the belief that children, being pure and spiritually close to the divine, can serve as messengers or temporary vessels for the kami.

Unlike Shichi-Go-San, participation in the chigo gyōretsu is not tied to a specific age. Any child may take part if they wish, often through a connection to the local shrine or community. Wearing flower crowns, colorful robes, and moving in rhythm with sacred music, these children walk ahead of the portable shrine as part of the divine entourage—a living symbol of harmony between the human world and the divine presence.

A Natural Relationship with the kami

To outsiders, Shichi-Go-San may appear as religious belief—but for many in Japan, it is simply part of life. It flows quietly beneath daily routines, surrounding us from birth like the air we breathe or the land we walk upon.

Sometimes, this relationship takes a more visible form. In shrine festivals, children walk as sacred figures through the streets, embodying the purity and presence of the divine.

Whether in a private prayer like Shichi-Go-San or a communal procession like the chigo gyōretsu, these rituals remind us that each life—yours, mine—moves through a sacred rhythm of becoming: of being held, protected, and slowly stepping into the flow of time, accompanied by something greater than ourselves.

Next Time

In my next post, I plan to explore the relationship between sacred space and inspiration—why jinja are the natural setting for life rituals.

But then again, I may change my mind and follow a different path. After all, my heart drifts with the seasons. I hope your heart finds freedom in nature, too, as you move through the week. See you next Tuesday. I welcome your comments and questions.

Thank you for the wonderful article as per usual! I wasn't aware of the phrase 七つ前は神のうち before. Japanese numerology fascinates me, with the 7-5-3 festival and the concept of Yakudoshi years, age seems to play a major role in many different festivals.

I'd love to hear more about cosmology and Shinto, I know I mentioned one of my favorite shrines is Hoshida Myōkengū, and it has a lot of Onmyōdō, and Buddhist influences there with a focus on stars and numerology.

I was very lucky to get to see Chigo events in Kyoto several times throughout the year. Knowing more about the beliefs behind them makes me appreciate them more. And I definitely believe that children in a way are more receptive to the divine, whether it be because they haven't yet learned of the mundane, or if they simply exist in harmony with the world around them in open eyed curiosity.

I hope if I ever have children, or for my nieces that I'm able to introduce them to Shinto and Japanese events by having them participate in a 7-5-3 event someday.

Looking forward to your next article.

Odd numbers as auspicious: I’ve been told this is because odd numbers can’t be split/separated (and are more stable than even numbers) but I don’t know if this is the reason or a modern rationalization for the Inyo-Gogyo law.

What do you think of the significance of the number eight? Specifically how it’s used to represent a value that may not be “eight”, such as 八百万, 八咫?

Could it be related to 八圭 (the eight trigrams), which represent a large number of permutations?