Moon 5 : Stop Doomscrolling, Look at the Moon

月がきれいですね 、一緒にお月見しましょう

Closing the Moon Series with Otsukimi(お月見)

The final chapter of this Moon Series is about Otsukimi—Japan’s moon-viewing tradition.

Here I’ll share not only its background but also simple ways to enjoy it yourself.

This year, October 6 falls on the fifteenth night of the eighth month in the old lunar calendar. On this night, the moon is called Chūshū no Meigetsu(仲秋の名月)—the Harvest Moon of Mid-Autumn. It is a time when many in Japan pause to gaze at the moon.

What Makes a “Meigetsu”?

The word meigetsu (名月, “illustrious moon”) carries a resonance that “full moon” alone cannot convey.

It is the moon of autumn, seen through clear skies and framed by stillness. For centuries, people have lifted their eyes to it, composing poems, or setting out offerings of dumplings and taro on their verandas and in their gardens.

In short, meigetsu is not only the full moon, but the full moon shaped by centuries of poetry, prayer, and human gaze.

Light as Blessing

Moon-viewing, then, is not simply the enjoyment of a scenic view. For the Japanese, it carries a resonance beyond beauty.

There is a word for this: ayakaru (あやかる). Written with the character 肖, the same as in “portrait,” it means to share in the fortune of something auspicious, or to wish for blessings by aligning oneself with it. Its root sense is “to borrow a pattern.” Patterns are visible. They are light. What we perceive as form is simply light reflected from objects and received by our eyes.

To look at the moon is to receive light itself, shaped like the moon.

The full moon shows this most clearly: a perfect circle of light. To gaze upon it is to feel blessed—by brightness, by quietness, by wholeness.

In Shinto shrines, a round mirror often stands before the sanctuary. The mirror is not the deity itself; the deity dwells beyond the closed doors of the inner sanctum. Yet the mirror reveals a truth: whatever appears in its reflection—every tree, every cloud, every part of the natural world—is already divine.

In the same way, the moon is not only a sight to admire. It is a mirror of blessing, one that reflects both nature and ourselves. And so, on the night of the meigetsu, people prepare offerings, sit together, and simply gaze upward.

How to Enjoy Otsukimi at Home

In Japan, the traditional moon-viewing setting includes dumplings, pampas grass, and the fruits of harvest. Each carries its own meaning, but you don’t need to recreate them perfectly—what matters is the gesture of preparing a place for the moon.

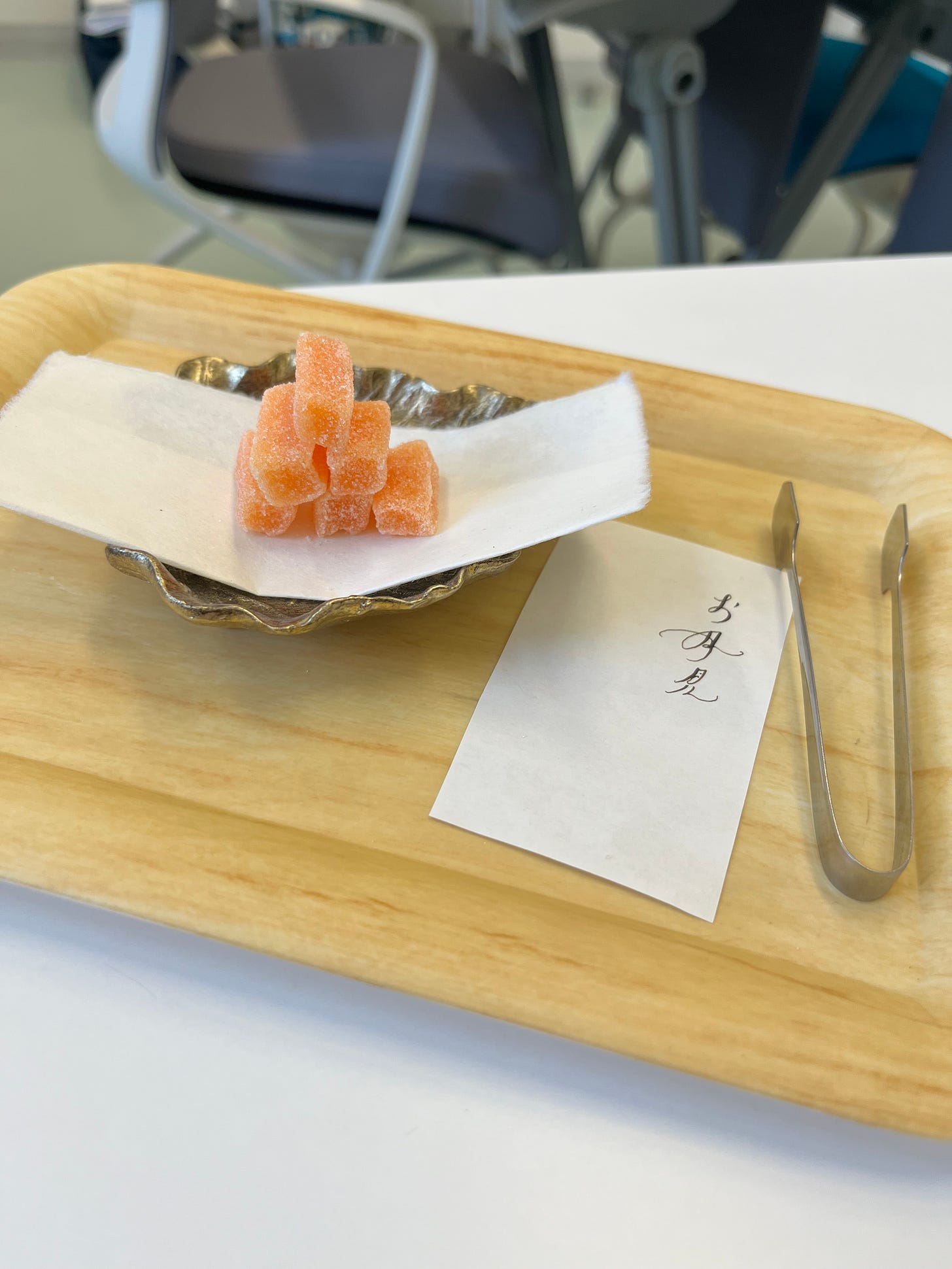

1. Tsukimi dango — moon-viewing dumplings

Round dumplings represent the full moon itself. Traditionally, fifteen are stacked in a small pyramid for the fifteenth night.

If rice flour is hard to find where you live, you can use mochiko, glutinous rice flour, tapioca starch—or even improvise with small pieces of bread dough. What matters is shaping the moon with your own hands.

2. Susuki — pampas grass

Susuki stands in for ripened rice stalks, symbolizing good harvest and protection from misfortune.

Outside Japan, you may not find pampas grass, but any tall, graceful grass—or even dried flowers—will echo the feeling of the season.

3. Seasonal produce

Taro roots, chestnuts, and persimmons are offered as signs of gratitude for autumn’s abundance.

Depending on where you are, you can substitute with local fruits—apples, pears, grapes. The important thing is to celebrate the harvest around you.

4. A place to wait for the moon

Traditionally, people sat on the veranda or in the garden. Today, a balcony or even a window will do.

Try turning off electric lights, light a candle or two, and let yourself wait for the moon to rise. The waiting is part of the ritual.

This “waiting” reminds me of summer evenings I recently spent in Paris. People gathered outdoors for apéritif time, enjoying the soft air, relaxed conversation, and the gentle passing of time. The background music was simply the hum of the city—voices, footsteps, clinking glasses.

In Japan, when we wait for the moon, the soundtrack is different: not the murmur of a city, but the chorus of insects rising from the grass. Yet the spirit is the same. In both places, you feel loosely connected to the wider world, suspended between day and night, between what has ended and what is about to begin.

5. Sharing food and time

Otsukimi is not about strict rituals but about being present. Share the dumplings and fruit with family or friends while gazing at the moon.

And if you are alone, it is still a beautiful time—have tea, write in your journal, or listen to music with the moon as your companion.

A Simple Recipe for Tsukimi Dango

If you’d like to feel the spirit of Otsukimi more closely, here is a very simple way to make the traditional dumplings:

Ingredients: 100 g shiratamako (glutinous rice flour) or mochiko, about 90 ml water

Steps:

Mix the flour with water until soft and smooth.

Roll into small balls.

Boil until they float, then cool in water.

Arrange on a plate—traditionally stacked like a little pyramid.

Plain dumplings are perfectly fine, but you can also sprinkle them with kinako (roasted soybean flour) or drizzle with syrup.

The Thirteenth Night

And yet, Japan’s moon-viewing is not limited to the fifteenth night.

There is another tradition, called Jūsan’ya (十三夜, the Thirteenth Night).

It takes place on the thirteenth night of the ninth lunar month—this year, November 5. Unlike the brilliant full moon of the fifteenth night, the moon on the thirteenth night is slightly waning, not quite perfect. Yet this imperfection has long been cherished as beautiful.

In fact, it was once said to be unlucky to view the fifteenth-night moon without also viewing the thirteenth. Together, the two nights form a pair: fullness and imperfection, completion and continuation.

If you have enjoyed Otsukimi once, let the thirteenth night be an invitation to look again. Even without offerings, simply stepping outside to gaze at that “not-quite-full” moon is to share in a very Japanese way of seeing beauty—finding harmony in what is slightly incomplete.

Looking Back and Looking Ahead

This post marks the end of the Moon Series. Over five essays, we have traveled together through myth and ritual, silence and light, reflection and practice. I am deeply grateful to all of you who have read, shared your thoughts, and even stepped outside to look at the moon with me.

Next month, a new journey begins: the Matsuri Series. What is a matsuri? How do the kami behave within it? What role do Sōdai (shrine leaders) and local communities play? Festivals are not only about color and sound, but also about how people and deities come together, shaping bonds of joy and gratitude. Where the Moon Series was quiet and contemplative, the Matsuri Series will place that silence side by side with music, drums, and the heightened energy of celebration—showing how stillness and festivity together create the rhythm of Shinto life.

Thank you for walking under the moonlight with me. Next, let’s walk into the Matsuri lights together.

Thank you for this beautiful journey through the moon. It helped me feel connected. I'm absolutely going to try and make moon dumplings! I'm new to Shinto and it's been life changing. Your essays have been a part of that and I am grateful 🙏

Thank you for this beautiful series. I feel I will return to it often. It reminds me – and I need reminding – the peace is always available to us if we only will stop for a moment.